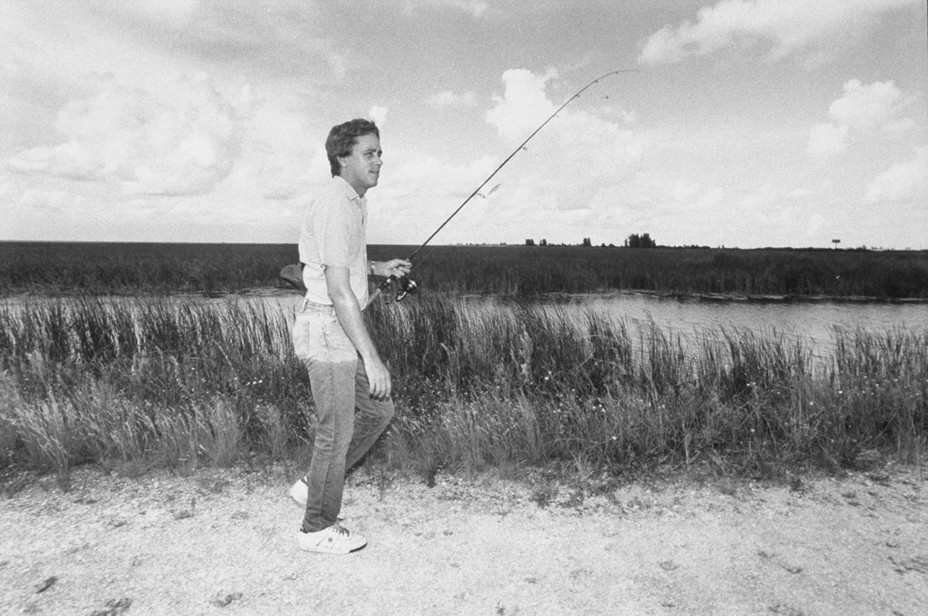

Nothing about Carl Hiaasen’s outward appearance suggests eccentricity. I’ve seen him described as having the air of “an amiable dentist” or “a pleasant jeweler” or “a patrician country lawyer.” He is soft-spoken, courteous, and plainly dressed. The mischief is mostly detectable in his eyes, which he’ll widen to express disbelief or judgment, or cast sideways to invite a companion to join him on his wavelength, raising his brows for effect. Every so often, he’ll say something that serves as a reminder of why his name has become synonymous with Florida Weird. We were eating turkey sandwiches at his kitchen table one afternoon earlier this year when Hiaasen told me about Rocky I and Rocky II, the pet raccoons he kept in the 1970s. Raccoons, he told me, resist discipline. “You can’t address them as you would a dog,” he said, “because they take it personally.” Things reached a breaking point with Rocky I when the raccoon climbed a bookshelf and tried to pry from the wall the first bonefish Hiaasen had ever caught, which his father had gotten mounted for him. “I had been at war with the raccoon for a while,” Hiaasen said, as though everyone knows what that’s like. “He was fucking with me.” Eventually, after chasing the animal through his tiny apartment, Hiaasen found Rocky “pissing all over the keys of my typewriter and looking me right in the eye.” To say that something is straight out of a Carl Hiaasen novel is by now only a slightly less clichéd way of saying that truth, especially in Florida, is stranger than fiction. At 72, Hiaasen has dozens of books to his name, virtually all set in the state. They have sold some 14 million copies in the United States and been translated into 33 languages. Hoot, a novel for children, has been wildly popular for two decades. The novels for adults form a genre unto themselves: part crime thriller, part satire, part unvarnished social commentary. His latest, Fever Beach, is just out from Knopf. A series based on Hiaasen’s novel Bad Monkey, starring Vince Vaughn, began streaming last year on Apple TV+, and another, based on Skinny Dip, is in the works at Max. Hiaasen’s books are animated in equal measure by righteous anger and a penchant for the absurd. He has spent decades trying to explain to his non-Floridian readers that reality provides much of the inspiration for his fiction. From 1976 to 2021, he covered crooked developers, corrupt politicians, and South Florida’s “cavalcade of crime” (as he once put it, sounding like a 1930s newsreel) for the Miami Herald, first as a reporter and then as a columnist. The job provided near-infinite grist for his imagination. Today, he drives around in a midsize white Cadillac SUV—the state car—with a bumper sticker that says WTF: WELCOME TO FLORIDA. His work can’t help but call to mind the “Florida Man” meme popularized a decade ago by an eponymous Twitter account. (A recent, real-world headline: “Florida Man Saves Neighbor From Jaws of 11-Foot Gator by Hitting It With His Car.”) But in recent years, the Florida story has gotten harder to distinguish from the national story. “When you’re writing satire, you’re looking for targets,” Hiaasen told an interviewer in 2016. “But you’re looking for targets that you can actually improve on in satire.” Hiaasen’s humor remains sharp and outlandish, but some of the darker currents of contemporary American life—the guns, the anger, the conspiracy theories—have become painfully personal. In 2018, his younger brother, Rob, was murdered in the mass shooting at the Capital Gazette newspaper in Annapolis, Maryland, where he was an editor and a columnist. Hiaasen still finds it difficult to talk about his brother’s death. The only way he knows how to process it all, he says, is to keep working. Nearly every day, he makes the short drive to the office he rents on the second floor of a generic-looking commercial plaza, puts on a pair of industrial-grade earmuffs, and writes. “The concept of retirement—I can’t even imagine,” he told me. What would he do with all the material? Hiaasen lives in a section of Atlantic-facing Florida known as the Treasure Coast. It got its name in the 1960s, after scavengers identified the offshore wreckage of 18th-century Spanish ships and began to turn up gold and silver coins and jewelry. Their finds, worth millions of dollars, sparked a treasure-hunting craze. The name endured, and soon a new treasure hunt—for waterfront property—began. It never ended. Driving around one morning, Hiaasen took me to see a cluster of tall condo buildings walling off the ocean from view. He quickly turned around to get us back to a less densely populated stretch of beach. “It’s just so fuh—” he began, before cutting himself off. “Ugly.” Hiaasen spends much of his free time fly-fishing for bonefish and tarpon, and many of the most memorable scenes in his fiction take place in nature. His protagonists are typically people who love the outdoors and its creatures, and are willing to go to great lengths to prevent the pillage of the environment by ruthless developers who have succumbed to what he calls, in one book, “the South Florida real-estate disease.” His best-known recurring character is a wild-haired, one-eyed man named Skink, who lives off the grid in the Everglades and eats roadkill for dinner; for fun, he shoots out the tires of tourists’ cars. Skink has an unlikely backstory: He is, in fact, an ex-governor of Florida—a man so principled, so incorruptible, that he was driven to exile in the wilderness after making himself the archenemy of “the people with the money and the power,” who “viewed him as a dangerous pain in the ass.” Only a few trusted allies know his whereabouts or his true identity. When someone in the novel Double Whammy asks Skink who he is, really, he tells her, “I’m the guy who had a chance to save this place, only I blew it.” The earnestness would be too much if Skink weren’t such a lovable weirdo, more often at work devising plots to foil greedy speculators and invasive vacationers—burning down a theme park, for instance—than lamenting his own futility. Hiaasen’s books are not whodunits, exactly. Usually it becomes clear within 100 pages or so who’s guilty of what, and why. The question becomes what they’ll do next, and whether they’ll get away with it. A sense of cosmic justice, shot through with dark humor, pervades these novels: Many of the bad guys end up suffering at the hands of nature itself, especially when they have tried to subdue it. In Skin Tight, a great barracuda bites off an antagonist’s hand. In Native Tongue, a loathsome theme-park security guard drowns after being raped by a sexually frustrated captive dolphin. In 2020’s Squeeze Me, invasive Burmese pythons keep turning up near the Palm Beach club owned by an (unnamed) American president; one of his supporters becomes a meal. Hiaasen’s skill as a writer lies less in the virtuosity of his sentence-level prose than in the exuberant strangeness of his plots and the inner lives of the people who inhabit them. This is a world of murderers for hire, sleazy lobbyists, incompetent lawyers, sketchy doctors, and thieving ex-husbands. Yet even the most detestable characters are more complicated than they appear at first glance: Hiaasen aims to create, as he once put it, villains whom “people don’t want to shoot right away.” Nor are Hiaasen’s good guys always the ones you’d expect. The hero of Strip Tease is a very beautiful, very smart stripper. (Women, in Hiaasen’s novels, tend to be both very beautiful and very smart.) The character Twilly Spree, who first appears in Sick Puppy and plays a major role in Fever Beach, has a hot temper, a rap sheet, and a multimillion-dollar inheritance from his “land-raping grandfather,” which he uses to bankroll environmental lawsuits. He has been banned for life from the city of Bonita Springs, having once sunk a corrupt city councilman’s party barge, but shows little remorse. “That slimeball loved his stupid boat,” he says of the incident. “So, yeah, I do enjoy ruining a bad guy’s day.” Hiaasen stopped writing his column in 2021, but with characters like Twilly and Skink—people who do things he says he’s fantasized about but would never dare attempt—his fiction remains an arena where he can play out his karmic Florida daydreams. “Some mornings I sit in the traffic and I think the best thing that could happen would be for a Force 12 hurricane to blow through here and make us start all over again,” he told a British newspaper in 1990. In a sly joke for anyone with a memory for storm names, the dedication page of his 1995 novel, Stormy Weather, reads simply: “For Donna, Camille, Hugo and Andrew.” As a child in the 1950s, in Plantation, Florida—then a tiny Fort Lauderdale suburb at the edge of the Everglades, now a city of nearly 100,000—Hiaasen would collect and sell poisonous snakes with his friends for $2 a foot (the rate for nonpoisonous snakes was lower). His boyhood menagerie also included a monkey, an opossum, and what he was told was a baby alligator, which he adopted when neighbors moved. The animal, technically a caiman, eventually escaped. Hiaasen told me he saw it again (he thinks) a couple of years later, when he was out fishing and looking for turtles in a nearby canal. He speaks about this childhood proximity to nature with a kind of nostalgic reverence. The destruction of that nature, seemingly overnight, to make way for shopping malls and highways felt personal. “It was so painful and infuriating to see,” he said. “It wasn’t that long ago that we were just hanging out, riding around in these pastures and going through these woods and creeks, and they just all got bulldozed.” A prank he played with some friends, pulling up survey stakes from a nearby construction site, later became the basis for Hoot, which is about a group of kids trying to protect an owl habitat from encroachment by a pancake house. But development was also the reason Hiaasen was born a Floridian. His paternal grandfather, also named Carl Hiaasen, moved from North Dakota to Florida in 1922 and helped found one of the first law firms in Broward County; his father became a lawyer too. Both represented developers, which was, Hiaasen says, what all lawyers in Florida did in those days. At Plantation High School, Hiaasen started a satirical newsletter called More Trash. In college, he transferred from Emory to the University of Florida to study journalism, and wrote columns for The Florida Alligator—mostly about politics, but with a sense of humor. He had watched Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show every night as a kid and mailed jokes to the show (he didn’t hear back). As Watergate and the Vietnam War filled the news, Hiaasen found late-night comedy to be a salve. “You always felt better: Okay, somebody else gets how stupid this thing is,” he told me. “It was just a relief.” He graduated right before Richard Nixon resigned, and soon began working as a reporter in Cocoa, Florida. Hiaasen had married his high-school girlfriend, Connie, and become a father at 18. His college experience had not been a typical one, but “I never felt like I missed anything,” he told me. He was always shy, and he liked the stability of being a husband and father. In 1976, Hiaasen took a job at the Herald, and he and his family moved back to Plantation. He was already writing fiction. At Emory, he’d met a recent medical-school graduate, Neil Shulman, who had creative aspirations. Hiaasen began working as Shulman’s ghostwriter; they collaborated on two comic novels (one of which was later turned into the movie Doc Hollywood ). A few years after starting at the Herald, Hiaasen joined the paper’s investigative team, writing articles with headlines such as “Developments Scar the Land, Foul the Sea.” He worked closely at the paper with William Montalbano, with whom he co-wrote three crime novels in the early 1980s. Soon he decided to write a novel of his own. Tourist Season was published in 1986. Its most memorable character is Skip Wiley, a Miami newspaper columnist who becomes so furious about “the shameless, witless boosterism that made Florida grow” that he starts a terrorist cell aimed at discouraging tourism and migration from the north. (“This is not murder,” Wiley says at one point, after he has kidnapped a retiree and is threatening to feed her to an endangered North American crocodile. “It’s social Darwinism.”) Hiaasen himself had just become a columnist. He didn’t kidnap anyone, but his skeptical, adversarial posture made enemies: the mayor, the Cuban community, civic boosters. A Miami city commissioner once introduced a resolution condemning him by name. The column became a thrice-weekly platform for Hiaasen’s opinions, albeit a mostly local one. His books—he went on to publish a novel every couple of years—gave him a national audience. He began appearing on talk shows to entertain viewers with tales of Florida’s real-life “freak festival.” “I get more complaints from people about Carl Hiaasen’s work than anything else,” the president of the Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce told the St. Petersburg Times in 1989. “I choose not to read his material.” Some reviewers complained that the genre blending was confusing, the plots too far-fetched. “If one critique dogs the author, it’s that he writes essentially the same book over and over again, upping the absurdity quotient each time out,” a Boston Globe writer observed in 2000. But readers kept buying the books. The Chicago Sun-Times described Hiaasen in the late ’90s as having gone “from cult favorite to best seller to brand name.” He also acquired a legion of hard-to-pigeonhole fans, among them Toni Morrison, Salman Rushdie, Tom Wolfe, Bill Clinton, and George H. W. Bush. More important to Hiaasen were the musicians he befriended after they read his fiction, including Warren Zevon and Jimmy Buffett. In 1995, Buffett paid tribute to Hiaasen’s work in a song called “The Ballad of Skip Wiley.” The more famous Hiaasen got, the more people liked to ask him when he was going to finally flee Florida. But he has never seriously considered living anywhere else. The sense of loss he feels for the Florida he once knew seems to be matched by a morbidly curious compulsion to witness the state’s continued degeneration, and a stubborn refusal to give up the fight. “There’s a circus element that’s hard not to watch living here,” he said. “It would be kind of a bummer not to see it unravel.” The joke about Vero Beach is that it’s where grandparents go to visit their grandparents. In the manicured neighborhood where Hiaasen has lived since 2005, the midsize SUVs are always gleaming, the hedges neatly trimmed. Walking around, I saw gray-haired men driving golf carts through unpaved lanes and passed a retirement-age woman wearing a white baseball cap embroidered in gold thread with a “47” and an American flag. At the public-beach entrance, two men scanned the sand with metal detectors, looking for treasure. None of these people seemed like Hiaasen’s people, exactly. He prefers being in a fishing boat to sitting on the beach, and though he lives down the street from an oceanfront country club, he no longer golfs. (One character in Fever Beach refers to golf as “the white man’s burden.”) He generally casts himself as a sort of winking misanthrope, which has made for an effective public persona, and isn’t far from reality. “Mark my words,” the legendary New York columnist Jimmy Breslin once said after meeting a young Hiaasen. “He has killed people.” Hiaasen is, at the very least, a cynical introvert. “There’s a glut of assholes on the loose,” he wrote in his 2018 book Assume the Worst: The Graduation Speech You’ll Never Hear. “The ability to sidestep and outwit these random jerks is a necessary skill.” What is it like to live with him? “Writers are impossible,” he told me. “My experience has been—” he laughed, and started again. “The feedback I’ve gotten is that they can be hard.” He and Connie divorced in 1996. In 2018, he separated from his second wife, Fenia; she and their son eventually moved to Montana. It was a lonely period. When Hiaasen was living in the Keys after his first marriage broke up, he’d started breeding albino rat snakes. This time, he had his two dogs, and his work. He was at his office on June 28, 2018, when he got the call from his sister. A man had entered the Capital Gazette newsroom—where their brother, Rob, worked—and opened fire. No one could reach Rob, and Hiaasen had a bad feeling. He drove home to watch TV, and eventually got confirmation: Rob had been among the five people killed. He was 59. (Prosecutors later said the gunman, Jarrod W. Ramos, was seeking revenge for a 2011 article the newspaper had published about his guilty plea in a harassment case.) Talking about the shooting, Hiaasen seemed torn between a brother’s anguish and a journalist’s critical remove. “There’s a cumulative amount of slaughter that we apparently have become so accustomed to. It’s so routine,” he told me. “You could hardly be totally surprised by it, given everything else that’s happened.” That same year, teenagers from Parkland, Florida, had boarded buses to Tallahassee and Washington, D.C., to share their grief and rage over the murder of their classmates at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School; Hiaasen had written about the students in his column. “You write about it and you write about it, and, of course, then Rob gets killed,” he said. As we talked about Rob, Hiaasen got quieter. He stared up to his left at the ceiling, then down to his right at the floor. At times he almost mumbled. “You always think about what the last seconds would have been like, when the guy comes in, blasting away,” Hiaasen said. “The way your mind works, you can’t help but imagine those things.” After Rob was murdered, Hiaasen started seeing a therapist who specialized in grief. He didn’t go to the trial, or to the sentencing, where the killer received five life terms without parole, plus additional prison time. “I didn’t think it would be good for anybody for me to be sitting there,” Hiaasen said. Though he’s read plenty of accounts of victims’ families feeling a sense of peace in the aftermath of a verdict like this one, he hasn’t experienced any such feelings himself: “That guy could suffer a horrible, gruesome death, and I wouldn’t shed a tear. But it wouldn’t dull any of the pain.” After a couple of months away from the newspaper, his byline returned to the Herald with a column about the shooting. “Each of us struggles with overwhelming loss in our own way,” it said, “so I wrote a column, which, after an eternity in this business, is all I know how to do.” Most of all, Hiaasen wanted to convey his respect for Rob as a writer and an editor. It was during that terrible summer of 2018 that he met the woman who would become his third wife. Katie was a recent Florida transplant, then 29, who was also divorced and worked in health-care IT. The two struck up a conversation at a restaurant and became friends. Hiaasen (who was 65 at the time) insists that he wasn’t looking for a younger woman; certainly, he told me, Katie wasn’t looking for an older man, let alone hoping to remarry. They started dating a year or so later, and got married at the courthouse in Key West in 2020, on a day when the weather was bad for fishing. That same year, Hiaasen published Squeeze Me—the book about pythons slithering around Palm Beach. He dedicated it to Rob’s memory. When I asked him if Rob’s death had made him more sensitive to violence, or more wary of employing it in his novels, Hiaasen said it probably had. Then he smiled and added quickly, “Don’t get me wrong. I want dreadful things to happen to the bad guys in my books.” After Squeeze Me, people started leaving angry comments on Hiaasen’s Amazon page. “I’d like a REFUND!” one reviewer wrote, citing disappointment with “page after page of vitriolic and vituperative character assassination of DJT.” “Fiction should be escape, not an in your face political hit-job,” another person wrote. They felt betrayed—why did this author they used to turn to for a good laugh insist on mocking Donald Trump? Hiaasen found this response amusing, but it also confused him. “All I could think was, Had they not read anything I’d ever written before? How in the world could you be shocked?” His work, he said, has always been political. True, but in less polarized times, his work was political in less polarizing ways. Being anti-corruption, for instance, is a position that has traditionally been shared by a bipartisan majority, and Hiaasen has vilified politicians, real and imagined, of both parties. But at a certain point between the election of 2000, when the recount saga put Florida in the national spotlight, and the 2023 revelation that Trump was storing classified documents in a bathroom at Mar-a-Lago, something changed. You could no longer write satire about Florida’s dark side the way Hiaasen always has without writing, in some way, about national politics. And when the butt of the joke is the MAGA movement itself, some readers will inevitably take it as an affront. Fever Beach will not redeem Hiaasen with these readers. In the first chapter, we meet Dale Figgo, a former Proud Boy who was kicked out of the group after January 6, when he accidentally smeared feces on a statue of a Confederate general whom he mistook for Ulysses S. Grant. Shunned by the mainstream white-supremacist community, Figgo has started his own group, “Strokers for Liberty.” (The Proud Boys’ restrictions on masturbation—laid out, for real, in a handbook that became evidence in one of the January 6 trials—are a running joke in Fever Beach.) Because this is a Hiaasen novel, where dreadful things happen to dreadful people, Figgo’s attempts to run a militia prove disastrous. His clever and clear-eyed tenant and housemate, Viva Morales, is constantly thwarting his schemes. She throws away the trigger of his AR-15. She refuses to tell him how to spell Fauci for his flyers. Eventually, she teams up with Twilly Spree—he of the inherited millions, short fuse, and habit of sponsoring environmental lawsuits—to infiltrate and take down the “confederacy of bumblefucks.” Hiaasen’s hope for his fiction, as he told me more than once, has always been that it will make people laugh for the right reasons. He wants his readers to have the same comforting experience that he did watching Johnny Carson all those years ago: You’re not crazy. The world is. Those who think the way Hiaasen does will no doubt get some relief from seeing Dale Figgo have skin from his scrotum grafted onto his nose (long story) and, later, get tied up in a Pride flag. The Key West drag queens in this book turn out to be better with their fists than the pathetic Strokers. But who has the last laugh? At times, Fever Beach risks reading like liberal-Boomer fan fiction—a pleasing fantasy, but perhaps too quick to validate its audience’s worldview or, worse, to offer false reassurance that a majority of bad actors are, as Viva suspects Figgo of being, “too dumb to be dangerous.” In real life, most would-be Proud Boys don’t have cunning, progressive housemates who will throw away their gun parts. Some of them even have security clearances. “Futile gestures that feel good at the time. That’s my weakness,” Twilly says near the end of the book. When I asked Hiaasen about this line, he told me that he can relate to Twilly’s sentiment. But then he brought up Edward Abbey’s 1975 book, The Monkey Wrench Gang—a novel about a group of radical environmental activists who sabotage what they see as efforts to encroach on the land of the American Southwest; it became a touchstone for Hiaasen, as it is for Twilly. Just because a gesture is likely to be futile, Hiaasen seemed to be saying, doesn’t mean it isn’t worth making. This, ultimately, may be the reason so many readers keep coming back to Hiaasen. The humorist Samantha Irby, a Hiaasen superfan, told me she admires a man who, at a point in his career when he could easily coast on tales of “husbands and wives trying to kill each other,” has instead chosen to write explicitly political satire. “I know how to find NPR if I really want to bum myself out,” Irby said. “Reality with a side of escapism is a blessing for our fragile minds at this time.” Two days after Trump took office in January, a man in a red hoodie, a black MAGA hat, and large sunglasses stepped off a plane in Miami. Enrique Tarrio, the former leader of the Proud Boys, was newly released from federal prison after having been granted clemency by the president, and was now heading home. A few onlookers cheered, and he made his way out of the terminal to a waiting black SUV. The next night, Hiaasen was seated in the choir room of a Vero Beach church, riffing with his friend and longtime Herald colleague Dave Barry about Tarrio’s freedom and other recent news. Barry, who is also famous for his Florida-specific humor, was in town to headline a benefit at the church for a local literary foundation. Hiaasen was set to introduce him to the 600-person audience. As the old friends talked, I learned about the reptile egg that Hiaasen had given Barry for his 50th birthday, in 1997. They’d named the egg Earl; Barry was pretty sure it had had a snake inside, but his wife hadn’t wanted to wait to find out. He’d been forced, he said, to get rid of the egg before it hatched. Hiaasen had just gotten back from a short trip to the Caribbean. He and Katie had left the country, he said, because he simply couldn’t bear to watch the inauguration from Florida. They’d done the same thing a few months earlier for Election Day. Hiaasen described his behavior as “cowardly.” Did being away help take his mind off things, at least? I asked him. “I thought it would,” he said. “But there’s no hiding.” The news alerts still came through on his phone. Yet after decades of covering Florida and its politics, Hiaasen told me, “you sort of condition yourself not to be apoplectic.” You keep watching the circus, and you keep writing about it. Plus, he said, “I do have a certain amount of faith in karma.” Karma came up again when we discussed the people-eating pythons in Squeeze Me : No, real-life invasive pythons have never eaten any human beings. They have eaten large animals, though, and as the climate warms, they are bound to move north. So the novel’s plot, Hiaasen insisted, is not outside the realm of possibility. He smiled. “Trust in nature,” he said. This article appears in the June 2025 print edition with the headline “We’re All Living in a Carl Hiaasen Novel.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.